SERTIT: satellite imagery for the environment and crisis management

I’MTech is dedicating a series of stories to success stories from research partnerships supported by the Carnot Télécom & Société Numérique Institute (TSN), to which Télécom Physique Strasbourg and IMT belong.

[divider style=”normal” top=”20″ bottom=”20″]

The regional image processing and remote sensing service (SERTIT) has specialized in producing geographic information production for over 30 years. It is linked with the ICube[1] laboratory, a key partner for Télécom Physique Strasbourg, and is part of the Carnot Télécom & Société Numérique Institute’s technology platform offer. Its role is to transform raw satellite images into a useful source of information to provide insights into regional land planning, environmental and biodiversity management, or rescue and relief operations in response to natural disasters. Mathilde Caspard, a remote sensing engineer at SERTIT, explains the platform’s various activities.

The regional image processing and remote sensing service (SERTIT) has specialized in producing geographic information production for over 30 years. It is linked with the ICube[1] laboratory, a key partner for Télécom Physique Strasbourg, and is part of the Carnot Télécom & Société Numérique Institute’s technology platform offer. Its role is to transform raw satellite images into a useful source of information to provide insights into regional land planning, environmental and biodiversity management, or rescue and relief operations in response to natural disasters. Mathilde Caspard, a remote sensing engineer at SERTIT, explains the platform’s various activities.

The SERTIT platform makes it possible to produce geographical information: what does this involve?

Mathilde Caspard: We mainly use satellite images, which we analyze and use to obtain information to help different actors make decisions. Our service makes it possible, for example, to map the forest cover or bodies of water. We can therefore inform land planning choices by providing information about the environment. We also have applications linked to crisis management following natural disasters such as floods, fires, hurricanes etc.

What role does the platform play in crisis management?

MC: We take part in rapid mapping operations. These actions make it possible to quickly deploy satellites to produce post-event maps in a short time frame. The satellite images are used to extract geographical information about the events. This information is then provided to the agencies which manage relief operations. We contribute to such efforts in particular through the COPERNICUS Emergency Management Service (EMS) European program. If there were to be major flooding in France for example, the authorized French user, the General Directorate for Civil Security and Crisis Management (DGSCGC), would request that the European Union activate the emergency rapid mapping service. If the request is accepted, the European program calls on our services. We must then provide information about the extension of the flooding, road and bridge conditions, submerged buildings etc. in less than ten hours’ time. The SERTIT rapid mapping service, which is certified ISO 9001, is available 365 days a year, and 24 hours a day for this type of mission.

In concrete terms, how do you ensure that SERTIT can respond to the request so quickly?

MC: As soon as we receive satellite data, we begin the image processing steps. We’ve been in existence since 1986, so we’ve developed numerous tools to speed up production. For example, we have algorithms that allow us to quickly extract bodies of water in images. In the event of forest fires, other algorithms help us identify burnt areas and untouched areas. Then, we cross-check this information with other sources of data, such maps made before the disaster. This helps us identify destroyed buildings, or unusable roads. Once all this information has been extracted, we deliver information in the form of a map and files that decision-makers can use directly in their systems to organize relief efforts.

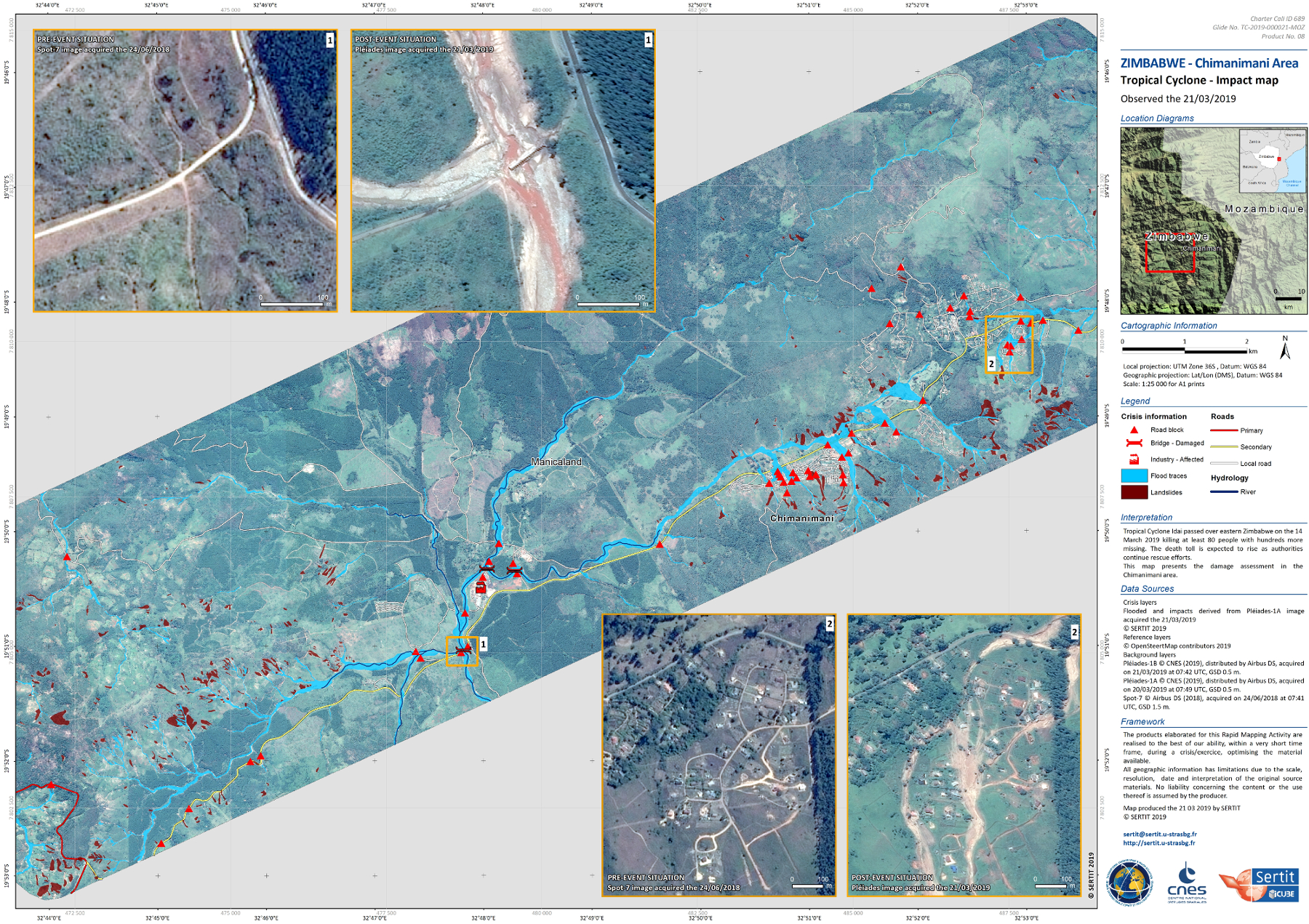

This example of a map produced by SERTIT illustrates the type of geographical information it can provide. The map shows the region surrounding Chimanimani in Zimbabwe, on 21 March 2019, following a tropical cyclone. SERTIT identifies blocked or unusable roads, damaged bridges, affected industrial zones, flooded areas etc.

This example of a map produced by SERTIT illustrates the type of geographical information it can provide. The map shows the region surrounding Chimanimani in Zimbabwe, on 21 March 2019, following a tropical cyclone. SERTIT identifies blocked or unusable roads, damaged bridges, affected industrial zones, flooded areas etc.

Do you only intervene in disasters that affect France?

MC : The European COPERNICUS EMS program is a consortium made up of several production sites spread out over France, Italy, Germany and Spain. Depending on the number and magnitude of the events, the services of several production sites can be called on at the same time. Our services may just as likely be called upon for disasters in France and in Europe as they may be for events elsewhere in the world. The European Commission may provide assistance to countries outside the European Union which are affected by natural disaster. In such cases, it calls on its rapid mapping service, since it must be able to determine how much assistance is required. Recently, for example we’ve worked on a cyclone in Mozambique, another in Australia, flooding in Iran, and fires in Kenya.

When SERTIT is not working on crisis management, what do the platform’s activities involve?

MC: We have a wide range of environmental applications. For example, we are frequently asked to carry out forest cover mapping. We quantify the clearings and deforestation at a given moment and compare it to previous data to track it over time . In Alsace we’re in frequent contact with foresters since they then integrate this data in their decision support tools to guide their cutting and forest maintenance as a result. In the same way, we measure urban areas to help local authorities with land planning. These are SERTIT’s long-standing activities. And we also receive occasional requests, for example, for specific biodiversity monitoring.

How do satellite images help monitor biodiversity?

MC: A good example is our work to help protect the European hamster. It’s an endangered species in our region since its habitat is threatened. An official program has been put in place to help reintroduce the hamster. Associations have worked to identify burrows and mark them with GPS coordinates. For our part, we have created survival indicators based on the geographic information associated with these GPS coordinates. For example, the hamster feeds exclusively on wheat and alfalfa and does not travel more than 300 meters from its burrow. We therefore assessed the areas in which hamsters emerging from hibernation were most likely to survive, based on the burrows’ surroundings. In addition to this activity, we’ve also worked on fine-scale vegetation for the mapping the Eurométropole de Strasbourg. These maps were used to create ecological corridors allowing for the movement of species in urban areas.

Where does the satellite data that you use for SERIT’s various applications come from?

MC: The European COPERNICUS program has a fleet of Earth observation satellites with various characteristics — not just for rapid mapping for disasters. This is somewhat unique in the world because the images are free as well. However, they aren’t always very high-resolution images. So, at the same time, we also use commercial images provided by companies such as Airbus or DigitalGlobe, whose images are much higher-resolution. It all depends on the desired objective: rapid image capture, wide field, accuracy etc. And in certain rapid mapping cases, in addition to all this, we also have at our disposal images acquired through the “International Space and Major Disasters Charter” which brings together 16 space agencies. It allows for international collaboration to provide free satellite images to best contribute to relief efforts.

[1] ICube is a joint research unit between University of Strasbourg/CNRS/ENGEES/INSA Strasbourg.

[box type=”shadow” align=”” class=”” width=””]

A guarantee of excellence

A guarantee of excellence

in partnership-based research since 2006

Having first received the Carnot label in 2006, the Télécom & Société numérique Carnot institute is the first national “Information and Communication Science and Technology” Carnot institute. Home to over 2,000 researchers, it is focused on the technical, economic and social implications of the digital transition. In 2016, the Carnot label was renewed for the second consecutive time, demonstrating the quality of the innovations produced through the collaborations between researchers and companies.

The institute encompasses Télécom ParisTech, IMT Atlantique, Télécom SudParis, Institut Mines-Télécom Business School, Eurecom, Télécom Physique Strasbourg and Télécom Saint-Étienne, École Polytechnique (Lix and CMAP laboratories), Strate École de Design and Femto Engineering. Learn more [/box]

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!