How our Web browsing has changed in 30 years

Victor Charpenay, Mines Saint-Étienne – Institut Mines-Télécom

On August 5, 1991, a few months before I was born, Tim Berners-Lee unveiled his invention, called the “World Wide Web”, to the public and encouraged anyone who wanted to discover it to download the world’s very first prototype Web “browser”. This means that the Web as a public entity is now thirty years old.

Tim Berners-Lee extolled the simplicity with which the World Wide Web could be used to access any information using a single program: his browser. Thanks to hypertext links (now abbreviated to hyperlinks), navigation from one page to another was just a click away.

However, the principle, which was still a research topic at that time, seems to have been undermined over time. Thirty years later, the nature of our web browsing has changed: we are visiting fewer websites but spending more time on each individual site.

Hypertext in the past: exploration

One of the first scientific studies of our browsing behavior was conducted in 1998 and made a strong assumption: that hypertext browsing was mainly used to search for information on websites – in short, to explore the tree structure of websites by clicking. Search engines remained relatively inefficient, and Google Inc. had just been registered as a company. As recently as 2006 (according to another study published during the following year), it was found that search engines were only used to launch one in six browsing sessions, each of which then required an average of a dozen clicks.

Jade boat, China. Metropolitan Museum of Art, archive.org

Today, like most Internet users, your first instinct will doubtless be to “Google” what you are looking for, bypassing the (sometimes tedious) click-by-click search process. The first result of your search will often be the right one. Sometimes, Google will even display the information you are looking for directly on the results page, which means that there will be no more clicks and therefore no more need for hypertext browsing.

To measure this decline of hypertext from 1998 to today, I conducted my own (modest) analysis of browsing behavior, based on the browsing history of eight people over a two-month period (April-May 2021), who sent me their histories voluntarily (no code was hidden in their web pages, in contrast to the practices of other browsing analysis algorithms), and the names of the visited web sites were anonymized (www.facebook.com became *.com). Summarizing the recurrent patterns that emerged from these browsing histories shows not only the importance of search engines, but also the concentration of our browsing on a small number of sites.

Hypertext today: the cruise analogy

Not everyone uses the Web with the same intensity. Some of the histories analyzed came from people who spend the vast majority of their time in front of the screen (me, for example). These histories contain between 200 and 400 clicks per day, or one every 2-3 minutes for a 12-hour day. In comparison, people who use their browser for personal use only perform an average of 35 clicks per day. Based on a daily average of 2.5 hours of browsing, an Internet user clicks once every 4 minutes.

What is the breakdown of these clicks during a browsing session? One statistic seems to illustrate the persistence of hypertext in our habits: three quarters of the websites we visit are accessed by a single click on a hyperlink. More precisely, on average, only 23% of websites are “source” sites, originating from the home page, a bookmark or a browser suggestion.

However, the dynamics change when we analyze the number of page views per website. Indeed, most of the pages visited come from the same sites. On average, 83% of clicks take place within the same site. This figure remains relatively stable over the eight histories analyzed: the minimum is 73%, the maximum 89%. We typically jump from one Facebook page to another, or from one YouTube video to another.

There is therefore a dichotomy between “main” sites, on which we linger, and “secondary” sites, which we consult occasionally. There are very few main sites: ten at the most, which is barely 2% of all the websites a person visits. Most people in the analysis have only two main sites (perhaps Google and YouTube, according to the statistics of the most visited websites in France).

On this basis, we can paint a portrait of a typical hypertext browsing session, thirty years after the widespread adoption of this principle. A browsing session typically begins with a search engine, from which a multitude of websites can be accessed. We visit most of these sites once before leaving our search engine. We always visit the handful of main sites in our browsing session via our search engine, but once on a site, we carry out numerous activities on it before ending the session.

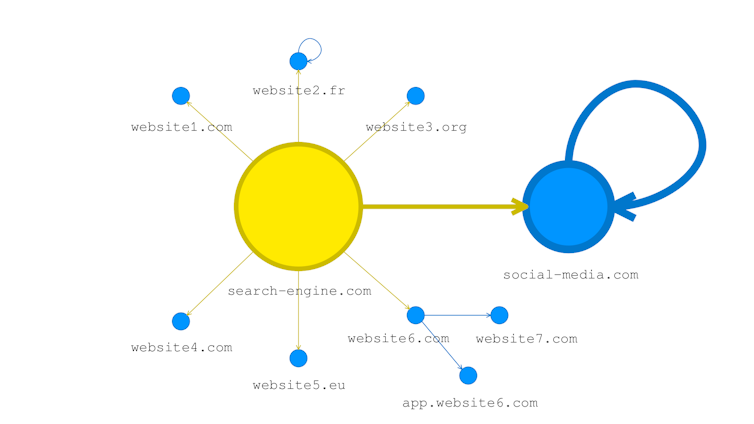

The diagram below summarizes the portrait I have just painted. The websites that initiate a browsing session are in yellow, the others in blue. By analogy with the exploratory browsing of the 90s, today’s browsing is more like a slow cruise on a select few platforms, most likely social platforms like YouTube and Facebook.

A simplified graph of browsing behavior; the nodes of the graph represent a website (yellow for a site initiating a browsing session, blue for other sites) and the lines represent one or more clicks from one site toward another (the thickness of the lines is proportional to the number of clicks). Victor Charpenay, provided by the author.

The phenomenon that restricts our browsing to a handful of websites is not unique to the web. This is one of the many examples of Pareto’s law, which originally stated that the majority of the wealth produced was owned by a minority of individuals. This statistical law crops up in many socio-economic case studies.

However, what is interesting here is that this concentration phenomenon is intensifying. The 1998 study gave an average of 3 to 8 pages visited per website. The 2006 survey reported 3.4 page visits per site. The average I obtained in 2021 was 11 page visits per site.

Equip your navigator with a “porthole”

The principle of hypertext browsing is nowadays widely abused by the big Web platforms. The majority of hyperlinks between websites – as opposed to self-referencing links (those directed by websites back to themselves, shown in blue on the diagram above) – are no longer used by humans for browsing but by machines for automatically installing fragments of spyware code on our browsers.

There is a small community of researchers who still see the value of hypermedia on the web, especially when users are no longer humans, but bots or “autonomous agents” (which are programmed to explore the Web rather than remain on a single website). Other initiatives, like Solid – Tim Berners-Lee’s new project – are trying to find ways to give Internet users (humans or bots) more control over their browsing, as in the past.

As an individual, you can monitor your own web browsing in order to identify habits (and possibly change them). The Web Navigation Window browser extension, available online for Chrome and Firefox, can be used for this purpose. If you wish, you could also contribute to my analysis by submitting your own history (with anonymized site names) via this extension. To do so, just follow the corresponding hyperlink.

Victor Charpenay, Lecturer and researcher at the Laboratory of Informatics, Modeling and Optimization of Systems (LIMOS), Mines Saint-Étienne – Institut Mines-Télécom

This article has been republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article (in French).

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!